I recently found myself reflecting on the wild corners that appear in the garden throughout the year, but especially in spring and summer, when we’re so busy tending to seedlings and new crops that diligent weeding falls by the wayside. It’s easy to view these untamed patches as a sign of falling behind, but wildness may offer more insight, diversity, and dinner than most of us realize.

Gardening is really the art of keeping a balanced unbalance: our human impulse to reduce chaos by weeding, planting, and taming meets the natural successional drive of nature. Ecology teaches that all open ground tends to move back toward forest, given enough time and absence of disruption—a process known as ecological succession. Human, animal, and environmental disturbances interrupt this, preventing our gardens from evolving straight into stands of brambles, shrubs, and then trees.

In our hurry to “tidy up” the apparent messiness that wild corners bring, we aim to simplify our gardens—cutting grass, digging out dandelions, chopping brambles—and reduce a complex ecosystem into something we feel we can fully understand and manage. But let some mystery remain. No matter how closely you observe your plants and soil, letting a patch of wilderness exist can turn your garden into a fascinating, self-renewing study in ecology, flavor, and resilience.

From pattern to detail: reading the wild

Those wild plants popping up in uncultivated corners aren’t random: they’re ecological indicators, reflecting the microclimates, soil conditions, water habits, and resilience of your plot. As any trained gardener or ecologist will note, you won't find the same wild plants in the Mediterranean as you will on a Scottish hillside, and you won’t see avocado seedlings in the wilds of Sweden any more than you’d expect to find larch in a tropical valley.

Though human management can modify many factors, understanding what wild species are “saying” about your garden is always invaluable. If you optimize for what is likely to thrive in your local context, rather than trying to force the impossible, you’ll always enjoy greater abundance with fewer inputs.

When planning your plantings, take stock of the site: soil structure, sun exposure, rainfall, drainage, existing vegetation, as well as potential animal visitors or pests. While field guides, neighbors, and local horticultural societies can help fill gaps, simply learning the most frequent wild plants in your garden provides a remarkable shortcut to understanding your land.

Common indicator species

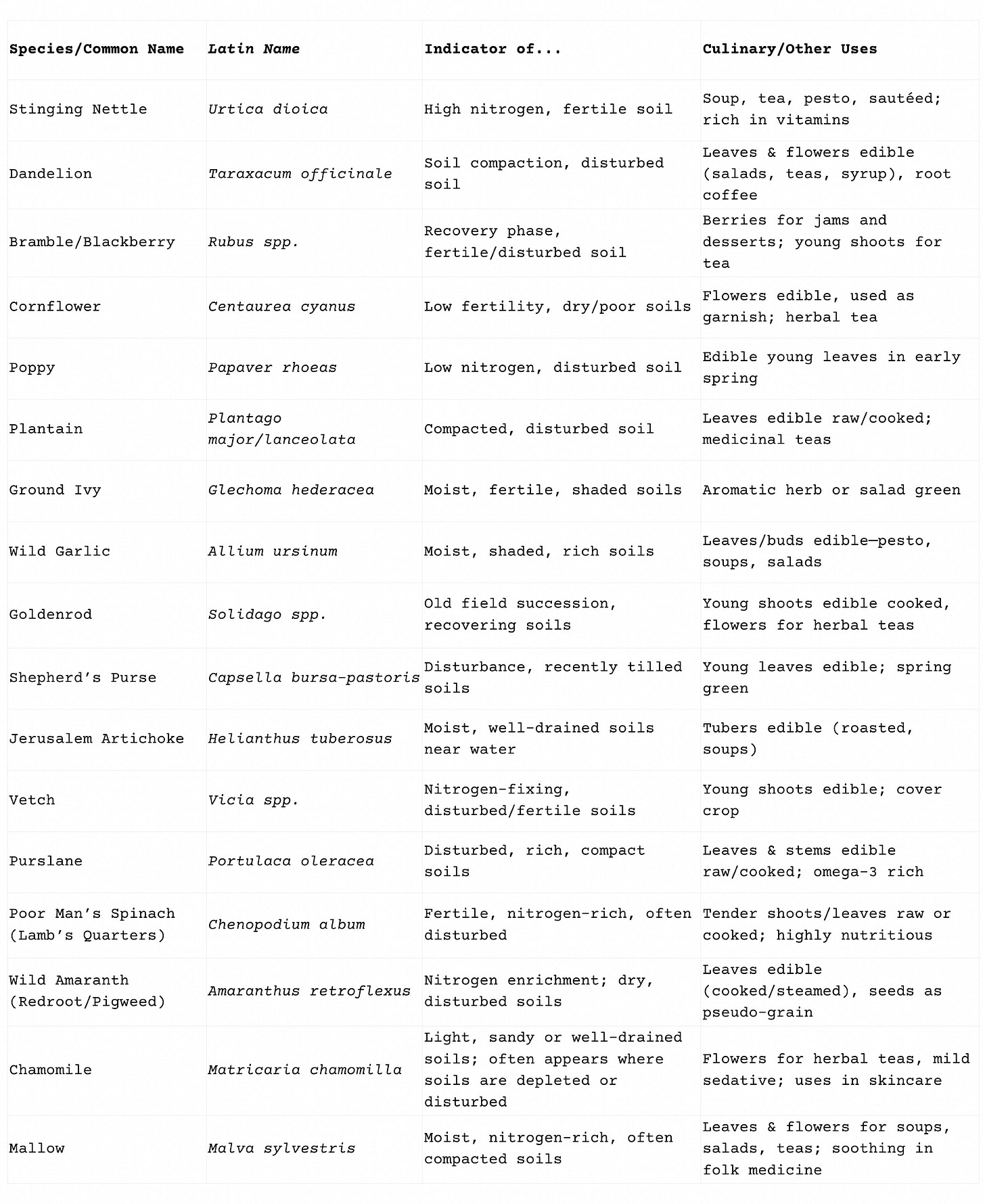

Many wild weeds are in fact indicator species: specialists in quickly colonizing disturbed ground, and excellent “reporters” on soil, water, and microclimate conditions. Observing them is a common practice in many styles of sustainable agriculture. Here are just a few:

These species “read” your soil and climate. If you see persistent dandelion and plantain, consider aeration; if nettle, you’ve got nutrients to spare. Where mallow or wild amaranth thrive, the ground is fertile yet often disturbed. And perhaps most importantly, many of these weeds are valuable food and medicine—offering vitamins, minerals, antioxidants, and flavors rarely found in commercial produce. Always check positive identification before harvest, as wild edible lookalikes can occasionally be toxic.

Small corners of biodiversity

Leaving some untamed strips in your garden isn’t necessarily about laziness, as it deliberately fosters habitats for pollinators, pest-controlling insects, and small wildlife. These areas are natural reservoirs for beneficial creatures, increasing both the ecological stability and productivity of your garden. Wild corners serve as vital refuges from which bees, ladybirds, lacewings, spiders, birds, hedgehogs, and amphibians can recolonize cropped areas following mowing, harvesting, or other disturbances.

What might look like chaos to us is, in fact, a self-organizing system that keeps pests in balance, supports pollination, and improves soil health through organic matter return and root aeration.

How to learn from our wild corners?

1. Observe first: Keep a garden log or take photos over the season. Notice which wild species emerge first in spring, and what fills gaps after cultivation.

2. Match crops to site: Where wild plants thrive, crops with similar requirements are most likely to succeed. If purslane and lamb’s quarters dominate, you have fertile and reasonably moist soil—great for many broadleaf vegetables.

3. Get foraging: Try adding a foraged wild plant or two in each week’s cooking. Wild herbs not only diversify your diet—they often bring health benefits and unique flavors hard to replicate with cultivated cousins.

4. Diagnose, don’t just weed: When certain weeds are persistent, address what they indicate—compaction, fertility imbalance, moisture excess—rather than just removing them.

5. Welcome diversity: If you allow part of your garden to go untamed, periodically notice the wildlife these patches draw. Pollinators, songbirds, predatory insects, and amphibians may all be spotted, especially in wild strips and edges.

Welcoming new allies

Every wild patch in your garden is more than a sign of work undone. It is a living indicator of soil and climate conditions, a free grocery and pharmacy, and a nursery for biodiversity. Instead of seeing wild plants as adversaries, see them as clues, guides, and delicious allies, once you get to know them. By allowing a measure of wildness, you cultivate not only a healthier ecosystem, but also a broader and deeper palette of flavors, remedies, and inspiration in your garden.

The postbox nest is the most adorable thing!